On June 24, 1948, the East Germans began their infamous blockade of West Berlin. The tremendous population of almost two million was in danger of starvation and suffering from a complete lack of electricity and oil.

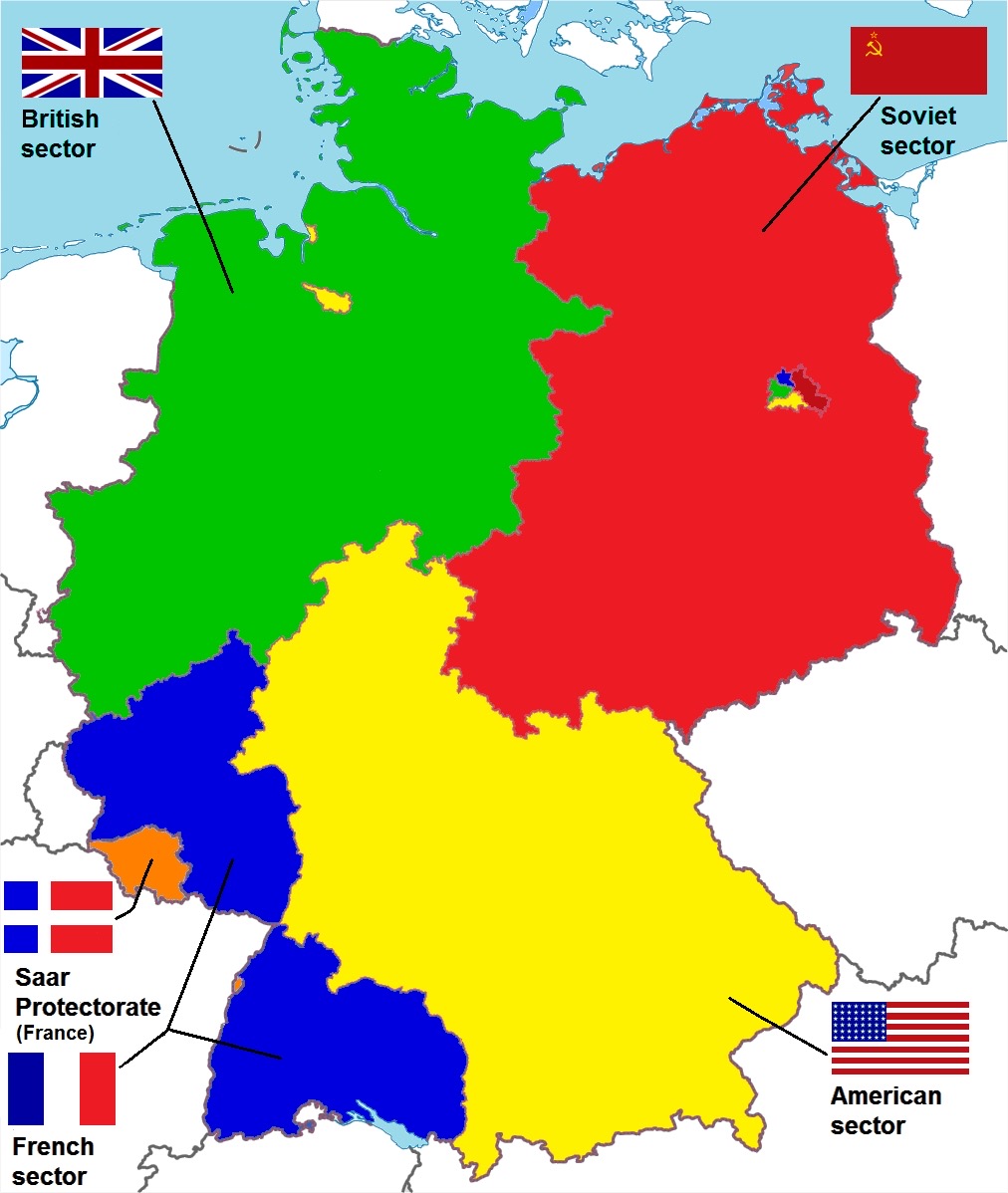

At the close of World War II, the Allies divided up the occupation of Germany, resulting in four zones: England in the northwest and west side of Berlin, France in the Saar and northwest Berlin, America in the southwest of both, and the USSR in the east of both. This meant that the western allies managed the western half of the capital city, Berlin, which was deep in the USSR’s territory. Initially, this was tense, but not particularly confrontational.

A few months prior to the start of the blockade, in March 1948, the western Allies – France, Britain, and the United States – had decided to unify their three segments into a single economic unit, Bizonia, under their common care and guidance. They concurrently introduced the mark as a new common currency in western Germany, excepting the capital city. The Soviets responded by withdrawing from the Allied Control Council. The situation escalated when the Allies elected to use the mark in West Berlin. The Soviets were threatened by the prospect of a united West German nation.

On June 24, 1948, the USSR declared that the four-way rule of Berlin had been voided by this change in currency, and commensurately, they began a blockade of the western section. All railways, roads, and even rivers like the Spree connecting West Berlin with the rest of the world were closed off. The Soviets intended to use the starving city as a bargaining chip, either forcing it to incorporate into East Berlin or using it to negotiate some other favorable change. On August 1, East Berlin began offering free food to those who would cross into their side, and although a few thousand defected, almost all trusted in the success of the airlift, and were rewarded.

To prevent disaster and the starvation of the city, the western Allies stepped in and on June 26, 1948, began flying in the necessary supplies. The Allied efforts did not stop at resupplying the city. Other planes were flying in and out of the rest of western Germany, shipping manufactured goods to other countries to boost trade and give vitality to the fledgling industry. By October 1948, Maj. Gen. William Tunner had transformed the originally disorganized operation into a systematic, successful system for long-term airlift, even receiving help from civilians to unload the C-54 transport aircraft.

A United States Air Force Pilot who was working with the Combined Air Lift Task Force, Gail Halvorsen, gave his only two sticks of gum to some children who were congregated at Tempelhof Airport on one of his missions. Regretting that he hadn’t had more to give them, he began to drop little bundles of candies in handkerchief parachutes on his approach to the airstrip. Soon, other pilots joined the official “Operation Little Vittles,” and manufacturers and Americans alike contributed to the snacks. This was a major propaganda success, and the “candy bombers” became famous throughout the world.

The notable success of the airlift increased tensions by confirming the robustness and response of the Allied military had not dropped off since the war. Both the Allies and the Soviets reinforced their military positions. The Soviets had 40 divisions on the ground in East Germany, so the United States sent bombers to Britain on standby, as their 8 divisions in western Germany would be in grave danger if the hostility escalated into war.

After a year and three months of having to fly essential supplies into the surrounded city, the former Allies were able to return stability to Berlin. On September 30, 2024, we celebrated the 75th anniversary of the lifting of the Berlin Blockade and the conclusion of the airlift. Luckily, this first Cold War flashpoint did not turn hot.