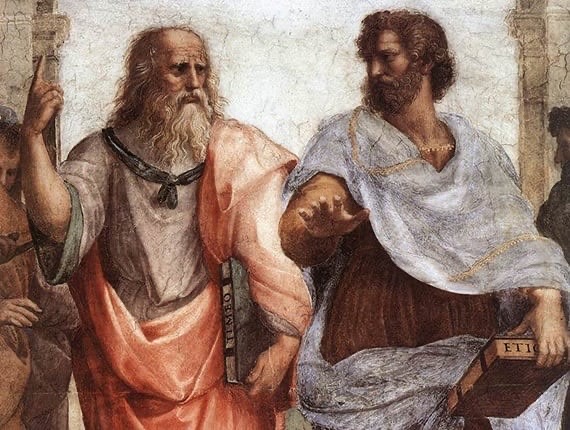

Early this year I wrote out an article concerning the Problem of Evil. Rereading it, I decided there was another topic hidden within it that I absolutely glazed over: “so what is evil anyways?” Once again, I raise up my usual disclaimer: I am no professional philosopher, just a high school kid with the power of Google and a whole lot of time on my hands when I stare at the ceiling at night, when I should be sleeping before a big economics test the next day. Nevertheless, this time, I’ll focus on a specific question of evil, referred to as the Euthyphro Dilemma. The source of this question, or at least where it was clearly articulated, is from Plato’s famous dialogue, Euthyphro. I have not read Euthyphro, I have only read its central question, paraphrased here: “Is good things that God commands, or does God command things because they are good?”

There’s a lot to work with here, of course. The first solution to the question is referred to as Divine Command Theory, one that when explained in different terms, seems to be a very obvious right answer to a significant portion of the theistic population. Divine Command Theory essentially states that God, as God, has supreme authority over right and wrong. Whatever he says is good, is good. Whatever he says is evil, is evil. Following what he says is good makes one a good person. Following what he says is evil, makes one an evil person. Being told to do something by God, and proceeding to not do said thing, is evil. That’s how Divine Command Theory works, it focuses on the three attributes of God I covered in my last article: omnipotence, omniscience, and omnibenevolence. Yet once again, it is omnibenevolence that comes under fire. A simple question arises. What if God commands people to do something that, frankly, to all conventional civil law, seems wrong? Something that seems evil? What if God commanded us to violently sacrifice a child? I know of three religions that will say, “well, he did.” The story of Abraham and Isaac, the offering of an old man’s son on an altar, by command of who else but God. Most people cite this story as proof of Divine Command Theory, proclaiming the righteousness of Abraham for his decision to attempt to carry out the sacrifice based on faith alone. By the simple command to kill Isaac, God makes the action of murdering a child good. That’s the logic of Divine Command Theory. God can do this because he is God, end of story.

Actually, I don’t think it is. I believe many people completely overlook the detail that God stops Abraham from actually carrying out the deed. Though the story places special emphasis on Abraham’s faith, God’s decision marks a very clear departure from Divine Command Theory. God stops Abraham from killing his own son, because, frankly, it is wrong. If it were truly right, purely because it was commanded then why did God stop Abraham? True, the command comes within the narrative of an incredible test

for Abraham’s faith. As it stands, it appears that God senses Abraham’s intention and his heart, and takes it as sufficient evidence that he has passed the test. He does not need to commit the act of evil to become good. It makes me wonder what would have happened if Abraham asked God if it were right to do this. But that’s enough of the Scriptural side. We’re talking philosophy here.

Well, hypothetically, say it were true that the command to sacrifice a child would automatically make it morally obligatory. If morality is subject purely to commands, then it is entirely arbitrary, and does not truly exist. It is subject to change at the whim of a singular being. This is a severe problem for the concept of the universe, to me at least. What would give God the authority over right and wrong simply by command? Some would argue that God’s omniscience allows him to know the true nature of right and wrong, and we simply cannot understand it. But if the true nature of right and wrong is simply what God commands, then saying God is good, simply means God does what he wants to do. And obviously, God knows what he wants to do, so it is not really a matter of omniscience. In a sense, morality is still “real,” but not concrete. Well, if it is not omniscience, then how about power? Omnipotence? Does God have the authority to change right and wrong, because he is the supreme all-powerful being, and the world is his own domain to govern? To phrase it more generally: might is right? I think, at least, when said that way, most, if not all of us recoil a little from the idea. Here is where I believe this theory is most flawed. This version of morality places power as the ultimate reality behind the universe.

So why would that be wrong? It errs by making God like the dictators of the 20th century. A tyrant, wishing only utter and absolute control of everything. Good is not done out of love, but fear. If this is truly what the world is about, then the path to fulfillment, to approach utter perfection, lies in getting as much power as we possibly can. As Nietzche puts it, “if there is a God, how could I bear not to become one?” And, if the universe is truly, fully about power, then I would be inclined to agree with him. Except that it isn’t. The far, prevailing sense that we can find in this universe is that we find fulfillment not in control and domination of others, but of service, sacrifice, and care. But beyond that realm of subjectivity, I think it is clear enough that there does exist a real morality. Thus, it appears the universe aligns more with the second “horn” of the dilemma, which apparently does not have a name as clear as Divine Command Theory.

The second horn of the dilemma states that God commands things because they are moral. This solves the omnibenevolence issue, because by choosing to act moral, logically, God is good. Some may argue it challenges the omnipotent problem, by limiting God’s ability to sin. I brought up this question once again with my teacher, Dr. Novak, who responded that it is not real power to commit evil. Evil, in itself, is an outwardly attractive, self-destructive, and unfulfilling perversion of goodness. God is in no way limited by not committing evil, instead, he holds greater power by overcoming it. The other major challenge to this argument is that it sets something, morality, apart from

God, and makes God subject to a higher authority that puts him within the universe, instead of outside it. Here, I would argue another way. Morality is the system of true right and wrong. Right and wrong, cannot exist without beings who make choices, who, apart from God, must exist within a universe to make choices in, like us. We make choices: right and wrong in a definite time and space, which exist within our universe. Without the universe, we do not make choices, and morality does not exist. From my point of view, God created the universe with a predefined set of “rules,” which we call morality, grounded in our innate nature and conscience. Going against morality goes against our nature, thus leaving us unfulfilled, and in a more technical sense, less like ourselves. Could God change these rules? I think so, but I think it would involve a fundamental change in how the entire universe works, as morality appears to be a fundamental cornerstone of the universe. If it were in line with ourselves to eat apples, because it is how our biology works, it would require quite a bit of changes to ourselves if we were meant to chug jet fuel instead. Thus, God commands us to act morally out of love, and out of care for our wellbeing. He wishes us to be moral because it is what will let us be most human.

Would it surprise you for me to say that all of this only scratches the surface of the issue? I may have made out a compromise leaning on the second horn of the dilemma, but there are still hundreds of other points of view that have been put forth and debated over the years. I do not claim I know everything, and definitely couldn’t write a dissertation on all of them right now. As it is though, I hope this opinion leaves you a good amount of food for thought.